Chinlone: A strong Rohingya passion for a Burmese ball sport

Chinlone, also known as caneball, is a traditional, national sport in Myanmar. It’s originally non-competitive with typically six people playing together as one team. The ball is normally made from handwoven rattan which sounds like a basket when hit. Similar to Hacky-sack, Chinlone is played by individuals passing the ball among each other within a circle without using their hands. However, in Chinlone, the players are walking while passing the ball, with one player in the center of the circle. The point of the game is to keep the ball from hitting the ground while passing it back and forth as creatively as possible. The sport of Chinlone is played by men, women and children, often together interchangeably. Although very fast Chinlone is meant to be entertaining and fluid, as if it was more of a performance or dance.

(Hamilton, Greg, Mystic Ball, Film, Black rice production, 2006)

Chinlone has played a prominent role in Myanmar for about 1500 years. Its style is performance-based because it was first created as a demonstrative means of activity for entertaining Burmese royalty. Chinlone is heavily influenced by traditional Burmese martial arts and dance, another reason as to why so much importance is placed upon the technique. As it is such an old game, many variations have been made to it, including hundreds of moves for maneuvering the ball. In addition to the original form of Chinlone there is a single performance style called “tapandaing”. While Chinlone had been widely considered by Europeans to be more of a game than an actual sport, international interest in Chinlone grew rapidly. By 1911 Chinlone teams were performing in parts of Europe and Asia. As spectators of Chinlone, Europeans derisively deemed it to be merely an entertaining game of indigenous people, too passive and not violent or masculine enough to be considered a sport.

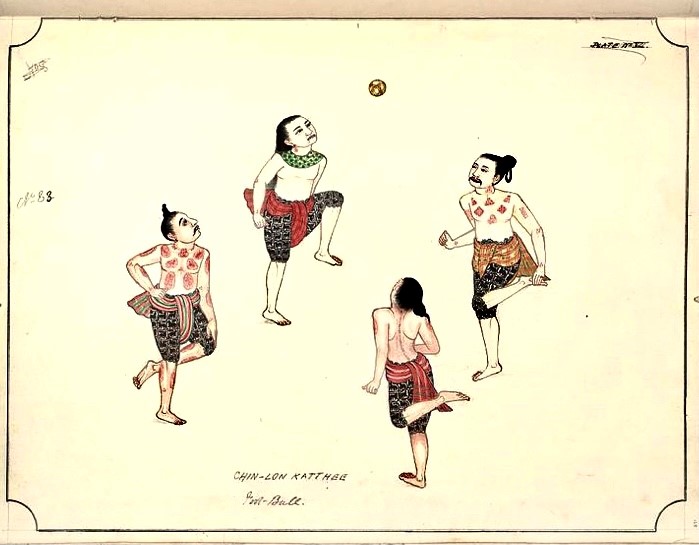

Watercolor painting of Chinlone by an unknown artist, 1897, The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

After gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1948, many British influences and cultural practices lingered, including those British sports such as Cricket and Polo. British colonialism dominant culture still weighed heavily upon Burmese life. From the 1960`s onward, starting with Ne Win`s military dictatorship, the government strongly promoted traditional and historical preservation in an effort to renew native cultural pride.

(Aung-Thwin, Michael & Maitrii, A history of Myanmar since ancient times, Traditions and transformations, Reaktion Books, 2012)

Rohingya youths playing Chinlone in a circle, photo credit Muhammed Shaker

Myanmar needed to focus on traditions that were unique to Burmese culture, free from any colonial influence. Chinlone fit this role perfectly, playing a key part in establishing Burmese nationalism. Myanmar began implementing physical education in schools, teaching children from a young age about traditional activities and sports like Chinlone as a way to educate and increase pride in their own culture.

(Aung-Thwin, Maitrii, Towards a national culture: Chinlone and the construction of sport in post-colonial Myanmar, 2012)

This was a small yet effective way in re-establishing unique Burmese life after many generations of colonial rule. With this newfound nationalism, Chinlone was finallyconsidered a real and cooperative sport.

Two well trained Rohingya teams playing Chinlone against each other, photo credit Zia Hero Naing

In 1953 the head of the Burma Athletic Association, U Ah Yein, was ordered by the Burmese government to write a rule book for Chinlone. These rules forced Chinlone to become more competitive, and the first official Chinlone competition was held in Yangon that same year. In addition to providing Chinlone with an official set of rules, U Ah Yein’s rule book claimed Chinlone to be unique to Myanmar only, as the birthplace of the game. While Chinlone does distinctively go back far into Burmese tradition, there are many similar sports closely related to it across many other Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand.

(Tomlinson, Alan, A dictionary of Sports Studies, Oxford University Press, 2010)

In 2013 the Southeast Asian Games were hosted in Naypyitaw, the capitol of Myanmar. Chinlone was included as a separate sport within the competition and was also featured in the closing ceremony. The inclusion of Chinlone was controversial, as other countries were not adequately prepared to compete in a uniquely Burmese sport.

(Creak, Simon, National restoration, regional prestige: The Southeast Asian Games in Myanmar 2013, The journal of Asian studies, 73, p.857-877, 2014)

Source of information: Wikipedia

Rohingya friends enjoying to play Chinlone on a narrow road of the camps, video credit Muhammed Shaker

Insight of Zia Hero Naing, founder of “Rohingya Sports and Fun” online, on Chinlone, 6th October 2021:

“Chinlone means a lot for the Rohingya. It’s a ball game that goes way back and belongs to our tradition and culture the same as it belongs to the Burmese. Rohingya love to play this game, especially the youths in our community. Even though the Rohingya in general identify themselves more with soccer, Chinlone plays an important role also and comes directly after soccer as the most favourite sport.

Usually Rohingya start to play Chinlone when they are around 14 years old. After the age of 30 it gets difficult to keep up physically with this demanding game. It gets harder with increasing age to maintain the moves that are required to keep the ball up in the air.

Of course the young boys love to kick the soccer ball first but whoever has a feeling for the ball loves to play Chinlone also. I personally love to play both myself.

Two Rohingya friends passing their time by practising Chinlone by themselves, video credit Muhammed Shaker

Many times we play Chinlone with three players against three players over a net, like a basketball net. This is always very exciting for us and we absolutely love to play as competing teams. Chinlone is usually organized between friends. These friends are mostly already connected through their passion for soccer. They manage the games by themselves and meet to play mostly in the evenings. These Chinlone appointments happen many times very spontaneous.

Back in Rakhine we all used to play Chinlone all the time. It’s easy to start, especially if you don’t have any space for a soccer field in the villages. It’s always great to play it also during the monsoon season. Many soccer fields are flooded or very muddy then which makes it impossible to play soccer. Chinlone you can play anywhere. So we just used to look for a space that was not muddy and got started. Chinlone can be played in the smallest space or corner. That makes it so convenient.

We seldom, if not never, played it with or against the Buddhist Rakhine though. We never got that close…

Here in the camps Chinlone was there always. Since it’s so difficult to find a bigger space that is suitable to play soccer, we play Chinlone instead. It can be played easily, just like that beside the road, the market or shelters.”

Rohingya playing Chinlone three against three in the evening, photo credit Ro Yassin Abdumonab